Upcycled 2045

I created Upcycled 2045, a visual novel game for children set in a dystopian year 2045, where they work in an upcycling workshop and slowly uncover a twist at the end of the story.

2024

—Laurensius Rivian Pratama - Solo Developer

Roles

My Role

- - Designed and programmed the entire game, from interface layout and resource economy to procedural material behaviour.

- - Wrote the story world and dialogue and created hand-drawn sprites and interface graphics.

- - Built the complex procedural texture and economy systems that connect 'waste recipes' to product value.

Theoretical Lens

- Environmental justice

- Futures literacy

- Systems thinking

Methodology

- Solo prototyping

- Systems simulation

- Narrative playtesting

Background

After working on the JFW Shoes project I realized how difficult it was to bring a single experimental object into the world, especially with limited factories, budget, and time. I still wanted to talk about material value and attachment, but I needed a more accessible and affordable medium. That pushed me toward education and toward tools I could explore on my own with just a laptop. I began to think that the next step was not another object, but a way to help people, especially children, see waste and materials differently.

Upcycled 2045 grew from that shift. I wanted to create an experience that feels playful yet still carries questions about circular economy and emotional value. A visual novel game felt like a good fit because it is cheap to distribute, can run on basic hardware, and lets me build branching stories without a large team. Through this project I started to explore how interactive narratives can become my testing ground, where I can observe how people respond to different futures of waste and upcycling using tools that are actually accessible in my current context.

I realised that education and campaigns which train us to be critical about the materials around us can begin in childhood, so I asked what might happen if I turned that idea into a popular interactive media for kids.

Overview

This game grew out of my material research at Waste4Change, where I spent months watching plastic waste turn into dense boards with very different textures depending on the mix of flakes, colours and layers. I realised that even so called low value plastic could become something beautiful and strong when the recipe is right, and that thought stayed with me.

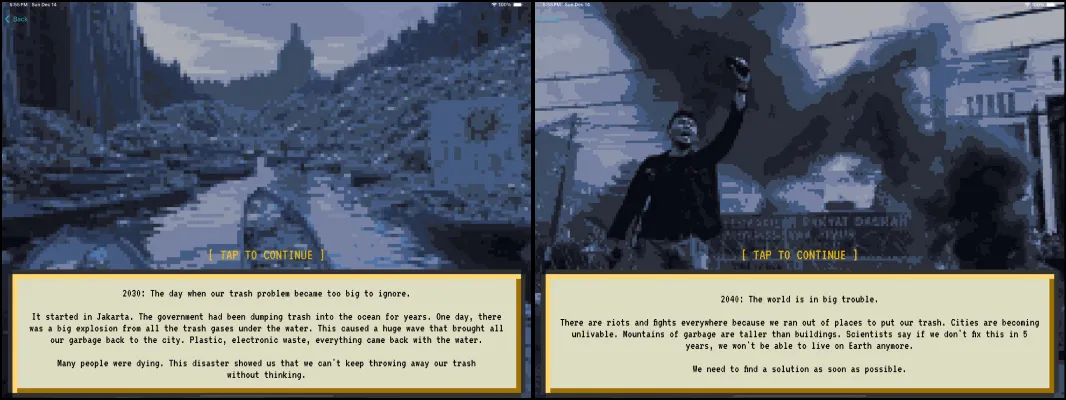

Storyline & Core Message

Core message

Upcycled 2045 is a warning disguised as a small game. The story starts with a hopeful idea that one brilliant machine and one dedicated worker can save the world by turning trash into useful objects. As the days pass, the player discovers that landfills keep growing faster than any individual effort. The game questions the fantasy of a technological saviour and asks the player to imagine change that goes beyond one heroic recycler. The key message is simple enough to remember after the screen turns off. The future is still open, but only collective action and cultural change can shift it.

World and characters

In 2030 a disaster in Jakarta turns buried waste and methane into a violent explosion that sends a wave of trash across the city. By 2040 mountains of garbage surround buildings, protests and conflict spread, and scientists agree that the planet may become unlivable within a few years. In 2045 an Inventor finishes a machine that can process any kind of waste into new products and hands it to the player, who works as a small shop clerk.

The player becomes the Clerk, an ordinary worker suddenly framed as the chosen operator of the miracle machine.

A mysterious Trader visits the shop with custom orders and promises access to buyers. The Inventor never appears in person during play yet shapes every part of the world. Their absence is important. The player is left with the legacy of a powerful tool but very little power over the system that surrounds it. Dialogue and small details in the shop slowly reveal how each character sees value, labour, and responsibility in a collapsing world.

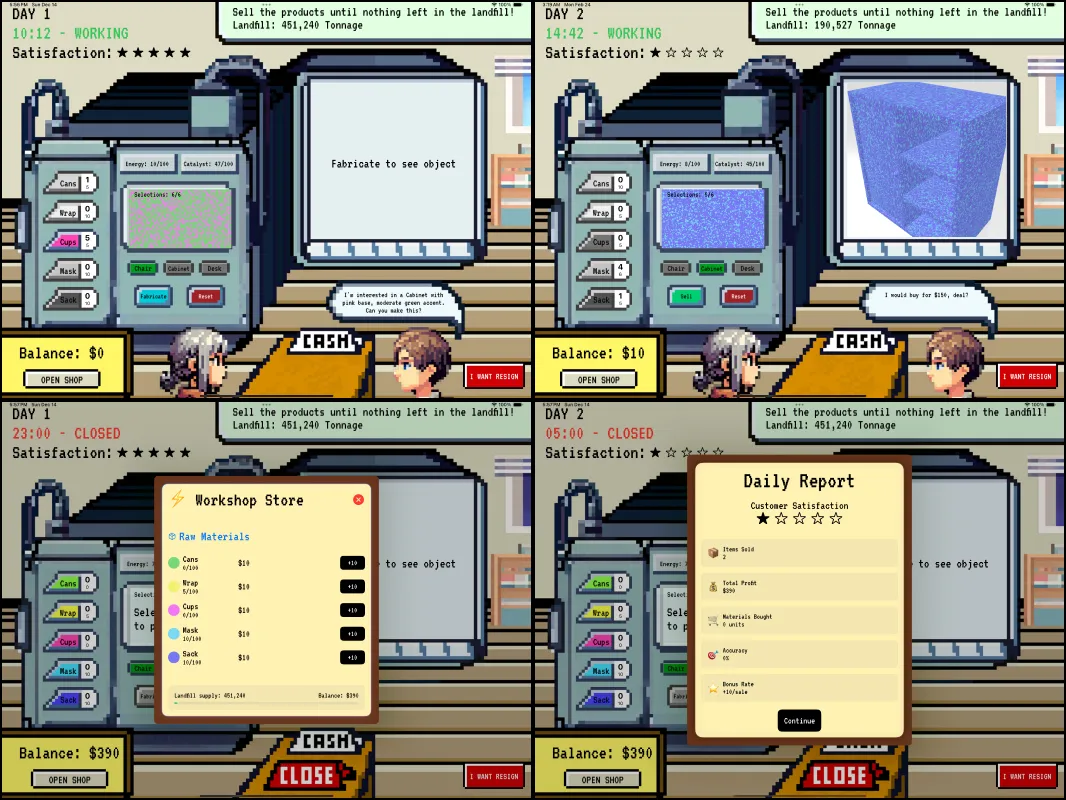

Game loop, emotional arc, and twist

Each in-game day begins with a fresh delivery of mixed waste, an energy bill, and a small window of time before the shop closes. Players run the machine, design products that match the Trader’s requests, balance electricity and catalyst costs, and try to keep the business alive. Counters in the interface show two stories at once. Local numbers rise in a hopeful way, such as products sold and small profit. Global numbers rise much faster, such as tons of waste added to landfills. The difference between these two scales creates the emotional arc. At first players feel clever and optimistic. Over time they notice that the graphs never bend in their favour and that skill does not change the outcome. The sense of control turns into frustration and then into reflection.

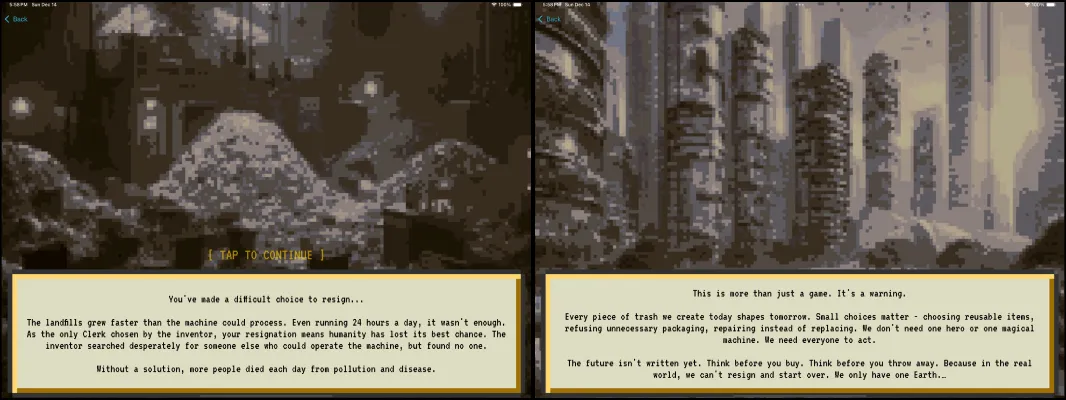

There is no hidden win state.

The only exit is a Resign button. Pressing it triggers the final sequence where the narrator explains that the machine helped for a while but the landfills still grew, governments still delayed, and humanity lost its best chance for an easy solution. The game then breaks the fourth wall and reminds players that they can close an app but cannot resign from the real world. The ending reframes every playful action as a model of real environmental activism, like how personal effort matters yet cannot replace structural change. I want to leave players with a quiet question, what would it take to act together before this kind of future stops being fiction.

Far in the future, sometime between 2075 and 2100, players learn that the Inventor also built a secret time machine, tried to fix the past, and died with the attempt. Humanity survives only in tiny numbers and remembers the Inventor as a mad person whose warning arrived too late.

Gameplay & Mechanics

Gameplay overview

The player plays as a day by day shop simulation where they run a small upcycling store in a collapsing future. Each day you open the shop, buy resources, turn mixed waste into products, and try to fulfil custom orders. Local numbers show small progress and profit while global waste keeps rising in the background.

Time and daily cycle

The game uses a compressed clock with two different speeds.

- The shop opens in the morning and closes in the late afternoon. During work hours time moves slowly so the player can think and act.

- During the night the clock moves much faster. The player cannot fabricate and mainly waits for the next day.

- At the start of each new day the world delivers a fresh load of trash. The total global landfill counter jumps by a large amount so the problem always feels bigger.

Rhythm of slow work and fast night makes the daily grind feel tight and slightly stressful. There is never quite enough time in a day and the world always drops more waste than the machine can clear.

Fabrication system

The core action in the shop is fabrication. The player combines waste materials to create a single upcycled product that received a specific order.

- Each click on a material adds one “unit” to the recipe. There is a strict maximum number of clicks so every choice matters.

- A special catalyst resource is slowly consumed as the recipe grows. The game nudges the player to find a balance between rich textures and limited catalyst.

- Every fabrication also uses one unit of energy, which links machine activity directly to the shop budget.

- The visual look of the product comes from the combination of materials. One main material becomes the base and the others appear as scattered speckles and shapes. The more mixed the recipe, the more noisy and complex the surface appears.

Orders, economy, and scoring

Orders arrive every day with a trader. Each order asks for a model, a base colour, an accent colour, and the strength of that accent.

- The selling price rewards good matches. A correct base colour gives a strong bonus. A correct accent colour adds another bonus. Matching the requested intensity of the accent adds a smaller bonus.

- Different product types have different values. A simple item brings a modest reward. A more complex model, such as a desk, brings a much higher reward.

- After a day of sales the game evaluates both volume and accuracy. Selling more pieces raises the volume score. Matching orders well raises the accuracy score.

- These two scores combine into a star rating from one to five. The star rating gives an extra money bonus for every sale.

I invited the player to experiment with recipes while still aiming for precise matches. It also makes it clear that careful listening to the order matters as much as speed.

Shop resources and upgrades

To keep the shop running the player must constantly buy raw materials and energy.

| Resource | Bundle size | Cost |

|---|---|---|

| Raw material | 10 units | 10 |

| Energy | 10 units | 15 |

| Catalyst | 10 units | 20 |

Running out of any resource blocks production until the player spends money on restocking. This keeps the game grounded in simple economics, which every fabrication decision is tied to a clear cost.

The interface also shows a set of upgrade options such as larger storage and more advanced fabricators. In the current build these work more as narrative hints.

I suggest a possible future where the shop grows into a larger factory, while keeping the present experience focused on small scale struggle.

Audio and feedback

Sound design supports the emotional arc of the game.

- A single ambient track plays in a loop during the work day. It creates a steady background mood that feels slightly heavy, like a long shift in a workshop.

- Short sound effects confirm important actions. Buttons, fabrications, and sales each have their own subtle click or chime so the player can feel progress even without reading the numbers.

- Opening and closing the shop each have distinct sounds. This underlines the daily rhythm and makes each new day feel like a new attempt.

- At the end of the day a report sound and summary screen mark a small moment of judgement. The player sees stars, profit, and landfill growth together and hears that evaluation land in their body.

Through this mix of systems the game encourages players to think with their hands. Every recipe, sale, and resource purchase feels like a small win, yet the overall structure keeps pointing back to a larger question. How far can individual optimisation go in a world that keeps producing more waste than one machine, or one person, can ever absorb.

Technical Implementation

Technical overview

Upcycled 2045 is built in SwiftUI with SceneKit for three dimensional product views. CoreGraphics draws textures at runtime so every object grows directly from the same recipe logic that frames plastic waste as a designable material.

Material and assets

Key sprites and interface elements are hand drawn in Procreate and pixel tools so the interface feels natural and slightly imperfect. Background scenes and icons use the same manual pipeline so they're connected to the idea of 'crafted' material. Music and sound effects come from GarageBand together with Suno AI tracks that I edit into loops so the soundscape follows the rhythm of each work day and the pressure of the growing waste around it.

Architecture and state

A compact model view structure holds time, resources, and global landfill values in observable objects that drive the interface in real time. Sessions reset on restart so each run works as a contained experiment in systems thinking rather than a progression based game.

Texture generation

The game turns each material recipe into a unique surface pattern. The first material the player chooses becomes the base colour to the whole object. Additional materials appear as scattered speckles on top of that base which drawn in different shapes and sizes. When the mix uses more accent materials, the surface grows denser and more chaotic, while simple recipes with one dominant material look calm and smooth. All textures are drawn on the fly, so no two products share exactly the same pattern.

What did I learn?

Reality of gaming market...

I got slapped with the reality of a crowded game market where gacha systems and competitive loops dominate gamers' attention. Most players expect a rush or a reward, while this game is designed to irritate them on purpose so the experience resembles being trapped in an unfair system. The project showed that reaching scale for a non addictive, reflective game will require different channels such as classrooms, exhibitions, or guided workshops instead of relying on organic growth in app stores.

I love the rapid tooling!

Modern tools allowed me to build a full simulation with hand drawn art, three dimensional previews, sound, and narrative arcs in less than two weeks as a solo creator with limited formal background in game development. SwiftUI, SceneKit, and audio tools like GarageBand and Suno AI lowered the entry barrier of creating interactive experiences. That speed reshaped how I think about research because I can move from concept to playable prototype quickly and use small games as test beds for questions about waste and meaning.

Interactive experiences as research probes?

I learned that a game can act as a compact research space for questions about value and responsibility. By adjusting numbers, recipes, and story beats I can observe how people respond to different futures of trash and circular economy. That insight now guides the next phase where interactive objects become probes in schools, exhibitions, and public workshops, and the reactions from those contexts feed back into my wider design and material practice.

What's next

Upcycled 2045 showed me how a small game can stage environmental collapse and questions of responsibility inside a safe frame, yet many people will never encounter that space. I started thinking more about moments outside the screen, when someone walks past a bin, waits at a corner, or spends a quiet pause with an ordinary object.

The next step is to translate the recipes, feedback loops, and slow frustration from the game into simple physical interventions that can live in classrooms and public spaces. I want these pieces to act as probes that test how people read materials, waste, and stories in everyday life, and to use their reactions as fuel for my wider research on how humans build lasting relationships with the inanimate.