JFW Shoes

We explored an experimental footwear concept for Jakarta Fashion Week using novel material fabrication and generative design that ergonomic and beautiful on the red carpet, while questioned the usual sacrifice of comfort in fashion.

2024

—Adrian Gan - Fashion Designer

Fioren Anthonia - Assistant Designer

Laurensius Rivian Pratama - Freelance Designer

Roles

My Role

- - Developed the initial concept space and created twelve design alternatives through sketching and generative studies.

- - Translated the chosen directions into detailed 3D models for both visualization and potential tooling.

- - Produced FDM prototypes to test proportion, heel ergonomics, and basic comfort on the foot.

- - Advised on material options and production scenarios within Indonesian manufacturing constraints.

Theoretical Lens

- Body ergonomics

- Material symbolism

- Critical fashion

Methodology

- Generative creative process

- Rapid prototyping

- Wear testing

Background

The JFW Shoes project grew directly from the Selayar Buoy work, which came out as successful project. I started to wonder what would happen if the same upcycling spirit entered high culture. I collaborated with one of Indonesia’s most prominent fashion designers for a major Southeast Asian fashion week to test whether upcycled material could stand on a red carpet usually reserved for exquisite materials.

High fashion often accepts discomfort as part of the aesthetic. Heels are expected to look striking even if they are difficult to wear. I began to question this habit, if discarded plastic could become a buoy that protects seaweed farmers, I wanted to see whether so called worthless material could rise to the level of couture footwear that also respects the person who wears it.

We aimed for a upcycled shoe that could sit on the red carpet while still paying attention to posture, pressure points, and balance. I explored forms that could carry both ergonomic support and a beautiful silhouette, using digital tools to search for shapes that a human designer might not propose at first glance. The challenge was to upcycle waste material as something precious without hiding where it came from.

We worked with low value multilayer plastics (un-recyclable!) that once wrapped food and everyday goods, the kind of packaging that follows people through ordinary moments. On the runway these fragments of daily life were transformed into a surface that looked refined from a distance but still kept subtle traces of their origin. Through this project I tried to show that upcycled materials can be beautiful, desirable, and gentle to the body while remaining honest about their past.

From Selayar’s experience, I wanted to see if the idea of giving new value to “zero value” material could also live in high couture. So I collaborated with one of Indonesia’s most prominent fashion designers to explore this potential.

Overview

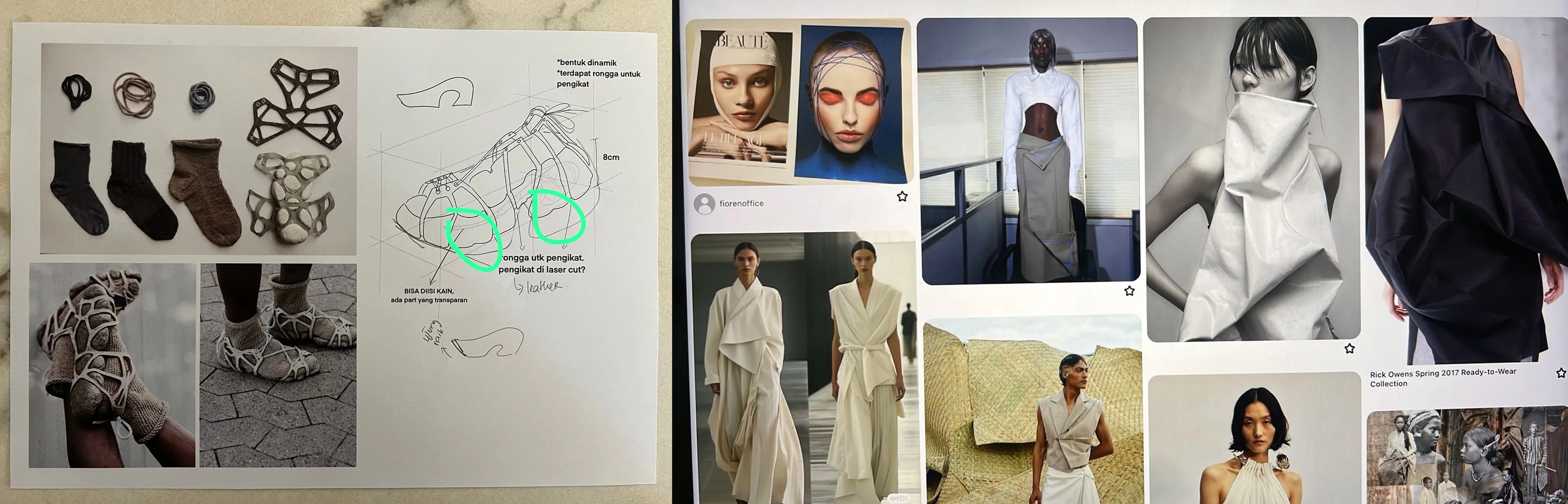

Fioren, assistant to Indonesian fashion designer Adrian Gan, approached me to design heels for a major show where the footwear needed to carry as much narrative weight as the clothes. The moodboard she shared combined cage like structures wrapped around thick socks, stone like shells around the foot, and sharply folded garments that behaved like soft architecture, all inside a dark, ritual atmosphere. They asked me to design the shoe as an expressive material system in direct conversation with the body rather than a neutral accessory.

Challenge

One of the main challenges was my lack of formal training in fashion design. I came from an industrial design background with a very pragmatic mindset, so I had to teach myself the semantics of beauty and how clothes and shoes communicate on the body. At the same time, that “blank canvas” of me questions the habits I did not grow up with and gave the project a slightly outsider perspective.

Design Process

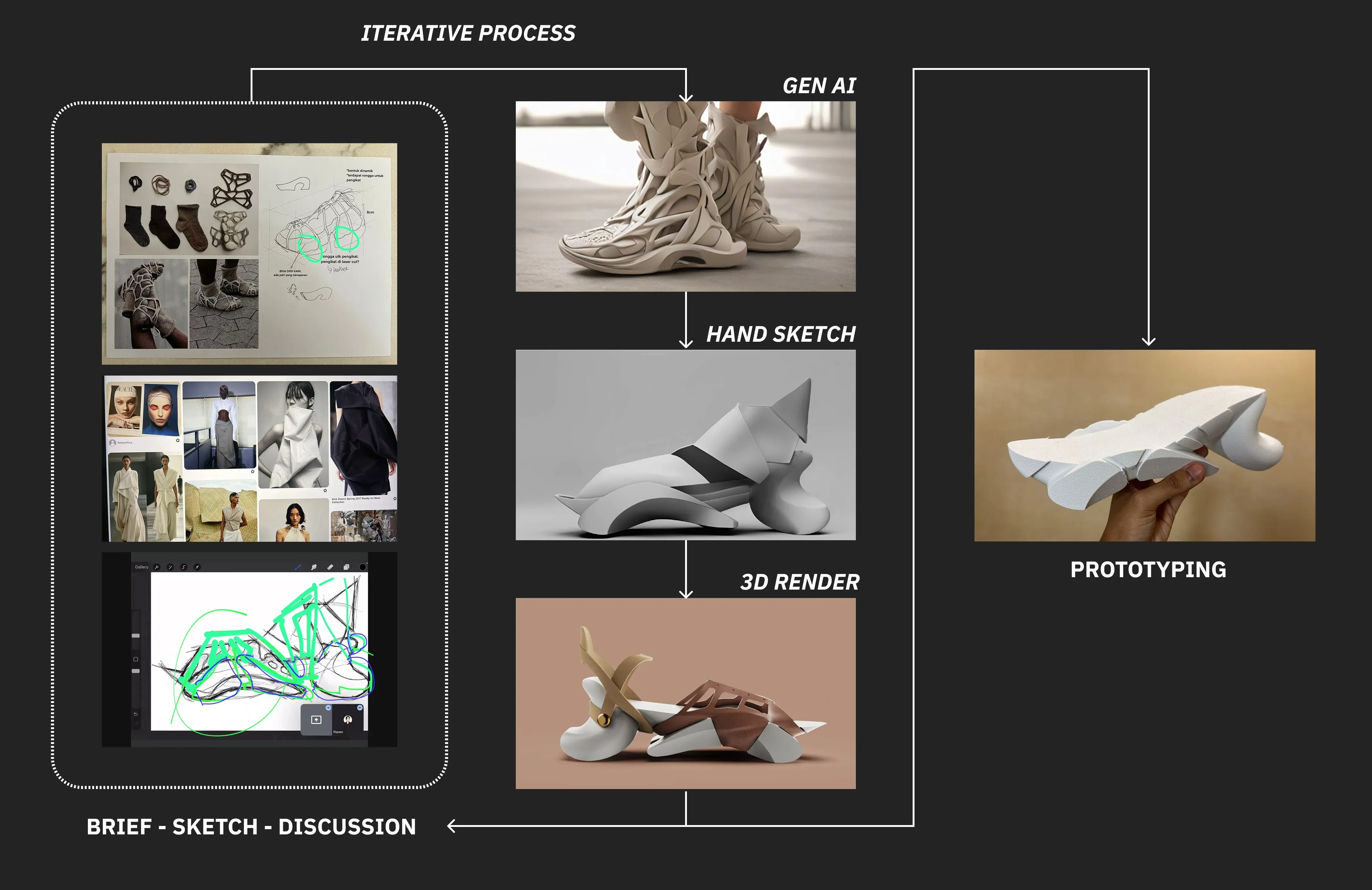

1. Low-quality generative design as my inspiration

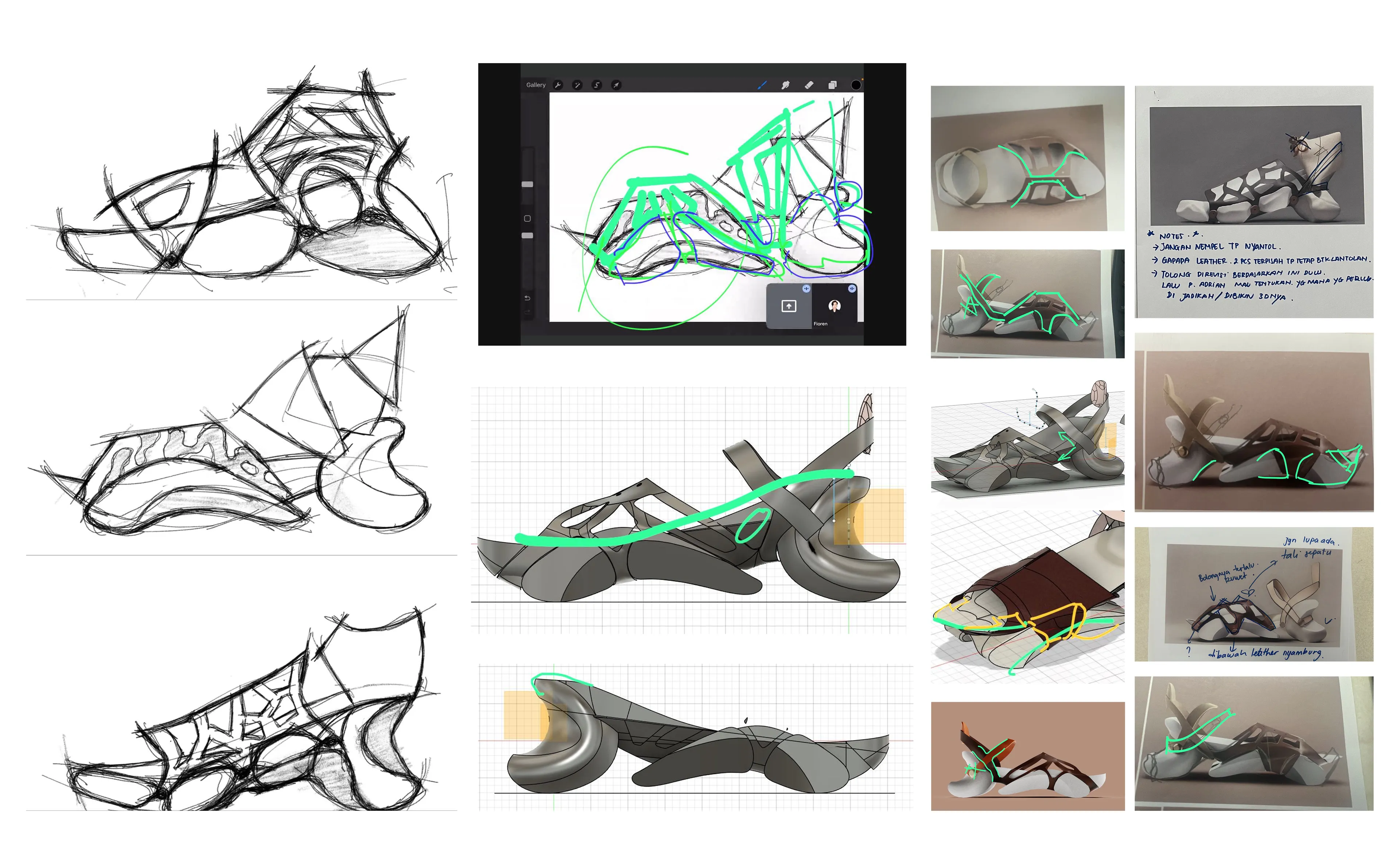

I used Stable Diffusion XL as an inexpensive tool for rapid exploration, which I deliberately working with a rough output that produced awkward and often unusable images. The distortions and the uncanny pushed the forms beyond my usual thinking and suggested structures that felt unexpected, which suited my interest in frugal engineering and finding new ideas from limited resources.

2. Rough alternative sketches Next I moved into a phase of rough sketching in Procreate and quick rendering in Vizcom. I tried to stay as exploratory as possible and did not think about manufacturing at this stage. I focused on loose ergonomics for the lower foot arch and on pushing the form to feel as edgy and unfamiliar as I could make it. From this process I produced around twelve alternatives, then Adrian chose three favourites that matched his vision, and those became the starting point for deeper refinement.

3. Final design refinement After Adrian had chosen three directions, we combined the strongest features of those options into one main design. We then refined the styling, the ergonomics, the laces, and the way the upper and sole hold the foot as a single flowing shape. During this stage I always kept manufacturability in mind, whether the form would later be made with additive or subtractive methods, and checked that the structure could support the body.

4. Final design render For the final stage I brought the chosen design into KeyShot and set it in a warm neutral scene so the focus stayed on the shoe. I rendered top, three quarter, and side views to study how the straps wrap the foot, how the sole meets the ground, and how the stone like base and leather cage relate. I used soft highlights on the sculpted sole and a matte finish on the upper to estimate how the shoe would appear under runway spotlights. It served as a clear reference for Adrian and the production team and marked the point when the design was ready to move into fabrication.

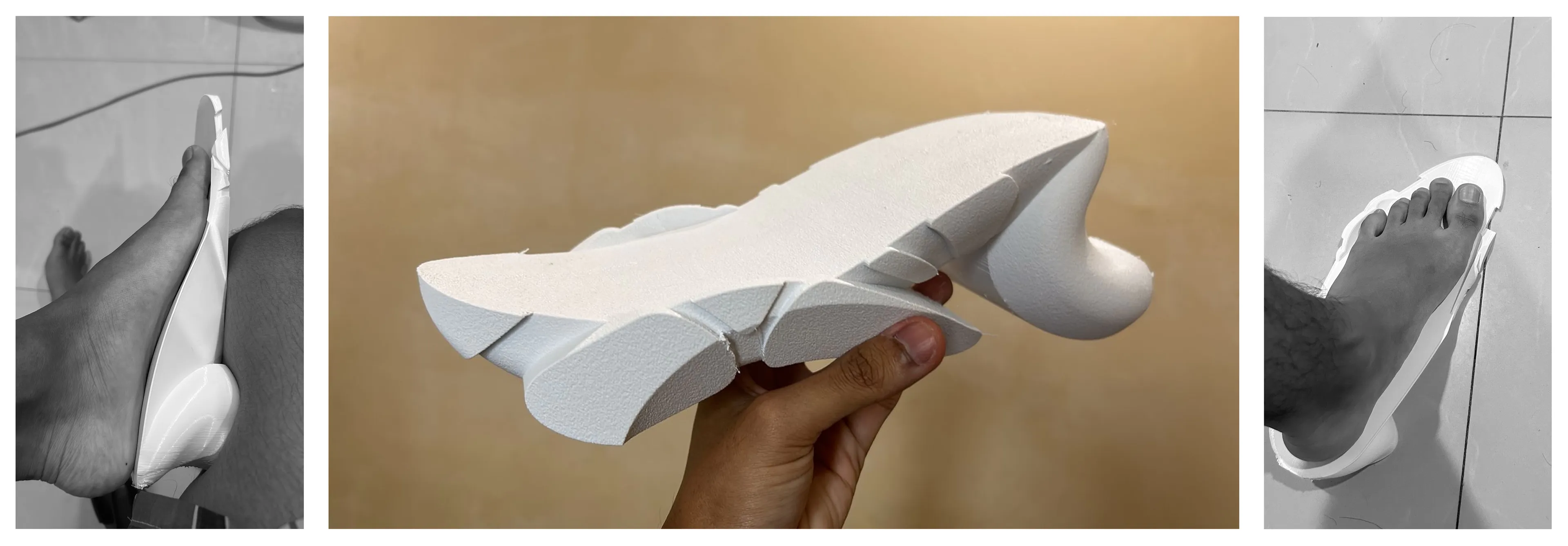

5. Rapid prototype pilot-testing We then ran a pilot prototype with my desktop FDM 3D printer. I printed several partial soles to study the heel arch, weight, and contact points on the foot, and we measured print time and material use to understand cost. On Cura I tested the experimental “fuzzy skin” setting to see how close we could get to a stone like surface straight from the printer. We also agreed to use PLA as the main material because it is derived from corn waste and more environmentally friendly than common filaments, so it became our basic standard for the project. These trials gave us enough feedback to finalise the leather lace pattern and set clear goals for full scale manufacturing.

Project Conclusion : Unfinished :(

In the end the project stopped at the design and prototyping stage.

During the wear tests the PLA sole felt too hard and heavy on the foot, so Adrian asked for a much softer, springy underlayer closer to foam than to a rigid 3D print.

To reach that comfort level the team explored industrial foam moulding in China, where factories quoted mould costs in the range of 500–1000 USD, which became difficult to justify for a run of only about twenty five pairs.

Several factories were also reluctant to take such a small order, which created delays and uncertainty that conflicted with the show schedule and slowly pushed the custom production plan off the table.

In the end Adrian decided to use a mix of shoes from his personal collection for the show, and my contribution remained as a completed design package and set of prototypes rather than a finished product on the runway.

My own explorations

Even after the client stepped away from production, I felt the project was too important to abandon so I continued to develop it as my own research. Without a show deadline I could slow down and look again at comfort, sustainability, and material storytelling in a more careful way. My aim was to understand how a heel could respect the body and still speak about the hidden life of materials.

Material Research

I explored several material options that could support the design goals in a more responsible way. I did research on pure PLA with internal cavities, silicone filling poured into 3D printed resin moulds, silicone based SLA resins, and gyroid printed PETG with shredded PET used as cushioning. The most promising direction came from stacked sheets of soft LVP multilayer plastic board that can be shaped as a solid block. Industry often calls this board unrecyclable because it mixes different plastic types, yet it still behaves as a thermoplastic and can be reshaped with heat and cutting. Each sheet also carries printed textures from its previous life, such as wood grain, marble patterns, or product graphics, so every offcut holds small traces of the spaces and objects it once belonged to. Turning that neglected material into high value soles felt like a precise answer to the brief. Also, by tuning the resin mix during board production, the softness and rebound can also be adjusted so the material becomes a way to study how hardness, comfort, and surface of the product.

Fabrication method

I compared several making methods including full 3D printing in flexible filament, hand carving foam, laser cutting stacked slices, and milling with a small router. I found that subtractive machining with a CNC router is the most realistic option for this phase. The process handles dense plastic boards at relatively low cost and gives precise control over the complex curves of the sole while staying fast enough for multiple pairs. In that way the design remains open to further iteration and stays complementary to the physical behaviour of waste based boards.

What did I learn?

This project only made sense in hindsight, when I looked at why it never reached the completion.

I should've read the local ecosystem better...

I learned that my ideas sit inside a very specific manufacturing reality in Indonesia. Experimental, small batch footwear with unusual structures is hard to produce here, and I did not study that limitation early enough. If I had mapped local factory capabilities, minimum quantities, and comfort standards at the start, I could have framed the design in a way that matched what was actually possible.

I underestimated the path from concept to shoe...

The design reached a refined prototype, but I did not build a clear path from concept to a soft, foam like, runway ready heel. I did not ask enough detailed questions about comfort, mould budgets, and the show schedule, so there was no shared plan that linked all three. That gap is on me. I now understand that for future projects I need to outline this bridge at the beginning, so everyone sees the technical and financial steps before we commit to a vision.

Turning my limits into a research direction!

When the commission stopped, I chose to keep going and look for an approach that fit my context more honestly. That search led me to low value multilayer plastic boards and CNC machining as a new pair of material and method for sculptural soles. The failure became an opportunity to explore a waste stream that industry usually ignores, and to treat it as a serious research subject rather than a fallback.

What's next

After learning from those earlier hurdles I wanted to shift my focus toward ways of elevating material value that were more scalable and personally accessible instead of depending on limited production systems. Designing buoys and couture heels showed me how fragile a project becomes when it relies on rare machines, specific factories, and small runs. I began to look for formats where I could still talk about materials, value, and attachment, but in a way that could reach more people with fewer production barriers.

I also want to go deeper into how people learn to value materials in the first place. Rather than only building objects, I need to design situations that change how people see everyday things, especially children and young adults who are still forming their sense of worth and permanence. My plan is to explore storytelling, interactive media, and simple open tools that can travel further than a pair of runway shoes, so the core idea of loving the inanimate can move into more minds.