Selayar Buoy

We worked with seaweed farmers in Selayar to turn plastic bottle caps into buoys using custom molds and open-sourced parts, so the same process could support small creative economy on the island.

2021

—Dr. Muhammad Ihsan D.R.S.A.S., S.Sn., M.Sn.

Harmein Khagi, S.Ds., M.Ds.

Laurensius Rivian Pratama

Muhammad Rayhan Arifinsyah

Roles

My Role

- - Explored the latching and locking mechanism using CAD software while considering the constraints in Selayar.

- - Ran fluid dynamics simulations and tested the 3D printed buoy in a home bathtub.

- - Explored and developed the design of the bespoke welding tools.

- - Created the animation and produced the project video.

- - Contributed to the commissioning training sessions on Selayar Island.

Theoretical Lens

- marine anthropology

- critical repair

- circular economy

Methodology

- participatory design

- material hacking

- in-situ testing

Background

After seeing how Indonesia has become a destination for the world’s leftovers, I wanted to work in a context where the consequences of overproduction are not abstract, but part of daily life. Selayar Island, with its seaweed farmers who rely on fragile, often makeshift buoys, showed me a very direct link between material, livelihood, and environment. I was curious whether something as mundane as discarded plastic bottle caps could be transformed into reliable tools that support both the ocean and the people who depend on it. For me, Selayar was a way to see if my love for “insignificant” materials could survive real constraints like rough seas, low budgets, and limited infrastructure, and still create something that matters.

I joined a research team in Selayar Island to explore how very mundane waste could gain new value when it supports seaweed farmers whose boats and tools depend on affordable materials.

Overview

Indonesia is an archipelagic country with a coastline of 99,093 kilometers, the second longest in the world after Canada. Lying on the equator, it experiences two monsoon-driven seasons, and these same winds and currents also carry large amounts of waste from surrounding lands and islands to its shores. Around 3.22 million tons of plastic waste in Indonesia remain poorly managed, much of it ending up as marine debris. This problem has become a national issue, leading the government, through Presidential Regulations No. 97/2016 and No. 83/2018, to set a target of 100% managed waste by 2025, with 30% reduction and 70% treatment based on a 3R (reduce, reuse, recycle) mindset. As part of this effort, academics are expected to contribute practical solutions. One approach is to turn difficult-to-recycle plastic into useful products for coastal communities. In the Selayar Islands, for example, appropriate technology is used to convert plastic waste into buoys for fishers and seaweed farmers, transforming a local pollution problem into a tool that supports both livelihoods and the marine environment.

Challenge

In Selayar, turning plastic bottle caps into buoys came with several challenges we had to tackle:

Degraded material quality : The plastic bottle caps had already been exposed to strong sunlight and UV radiation, which reduced their strength and consistency and made the moulded parts more fragile and brittle, but the final buoy components still needed to be watertight and reliable in rough sea conditions.

Compact, low-power, and repairable machinery : All machinery had to be compact enough to travel easily to a remote island by boat or truck. Because electricity on the island is limited and sometimes unstable, the machines needed to run on low power and rely on simple heating elements and small motors. The system also had to be repairable using off-the-shelf parts available in small local shops, since we could not depend on specialised technicians or imported components for maintenance.

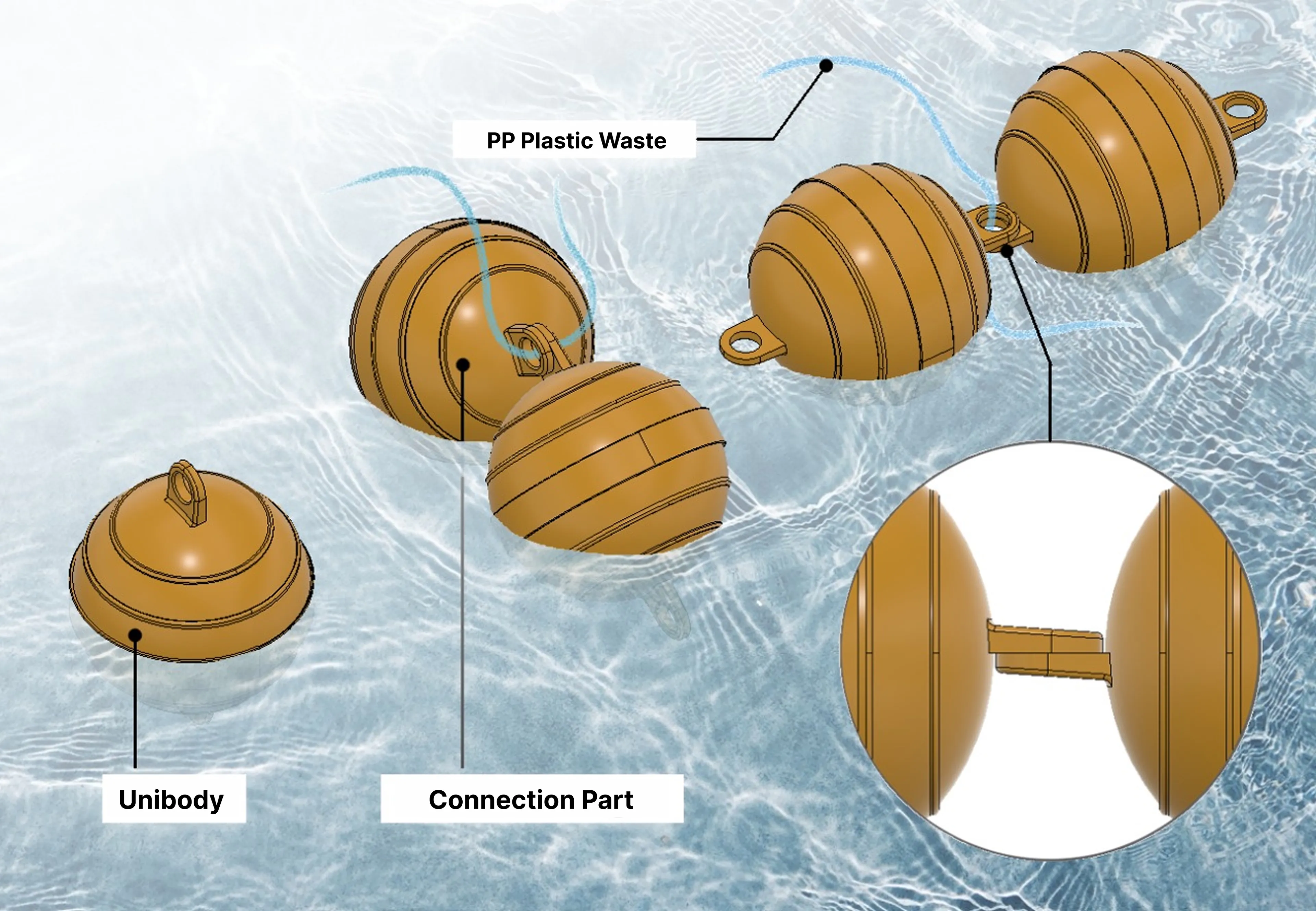

Strict cost and tooling limits : Our budget was very limited, so we could only build one simple mould. There was no option for complex male–female mould pairs or multiple sizes, so all parts needed to come from a single uniform tool, and the buoy shape and connection system had to work within this one-mould constraint.

Design Process

3D CAD Modelling

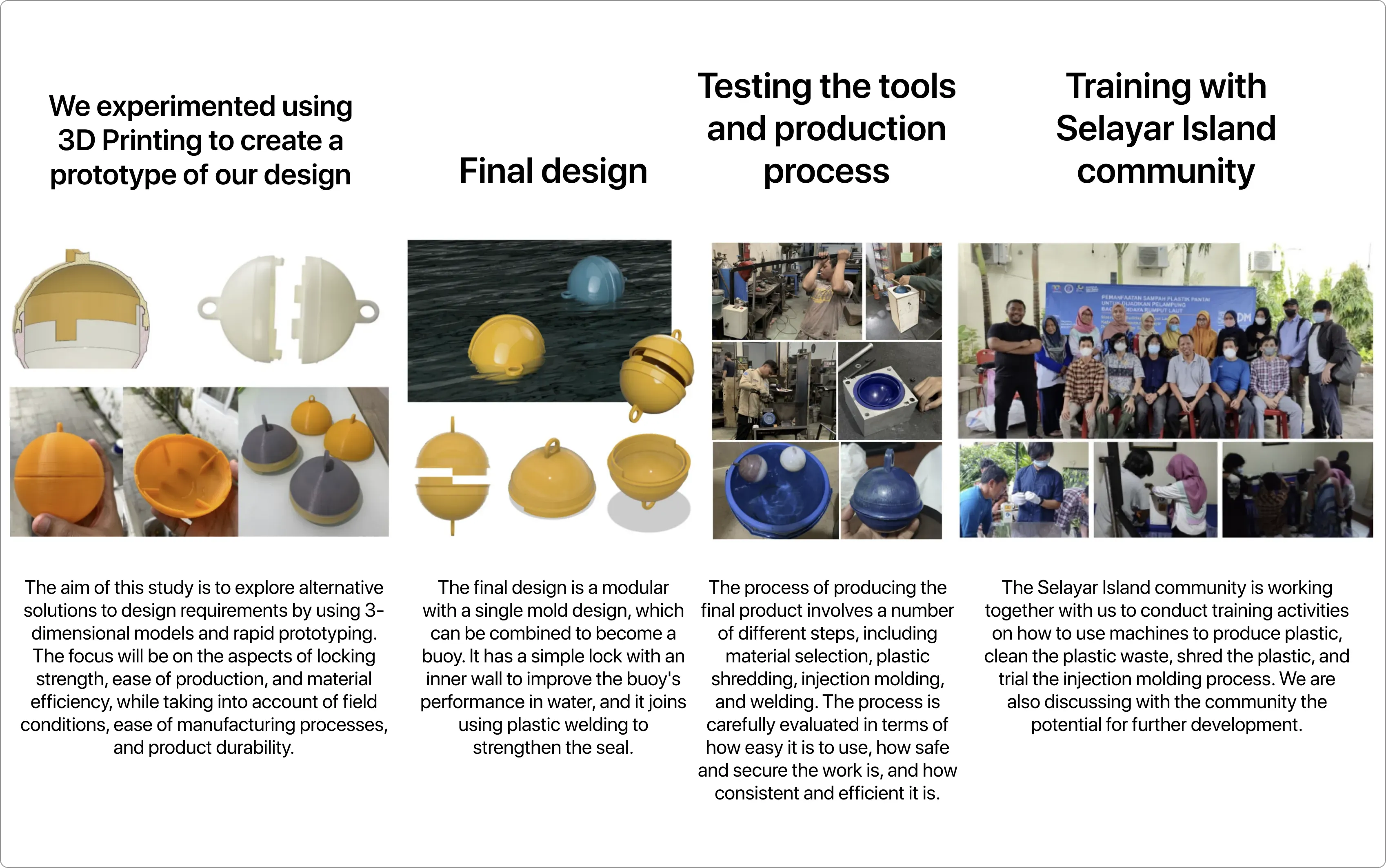

I 3D-modelled the buoy using Fusion 360 so the same file could be used for fluid simulation, 3D printing, and mould-making. We explored different wall thicknesses, simple locking geometries, and a single-mould split line that would minimise material use, make demoulding easy, and still leave enough internal volume for good buoyancy.

Fluid Simulation

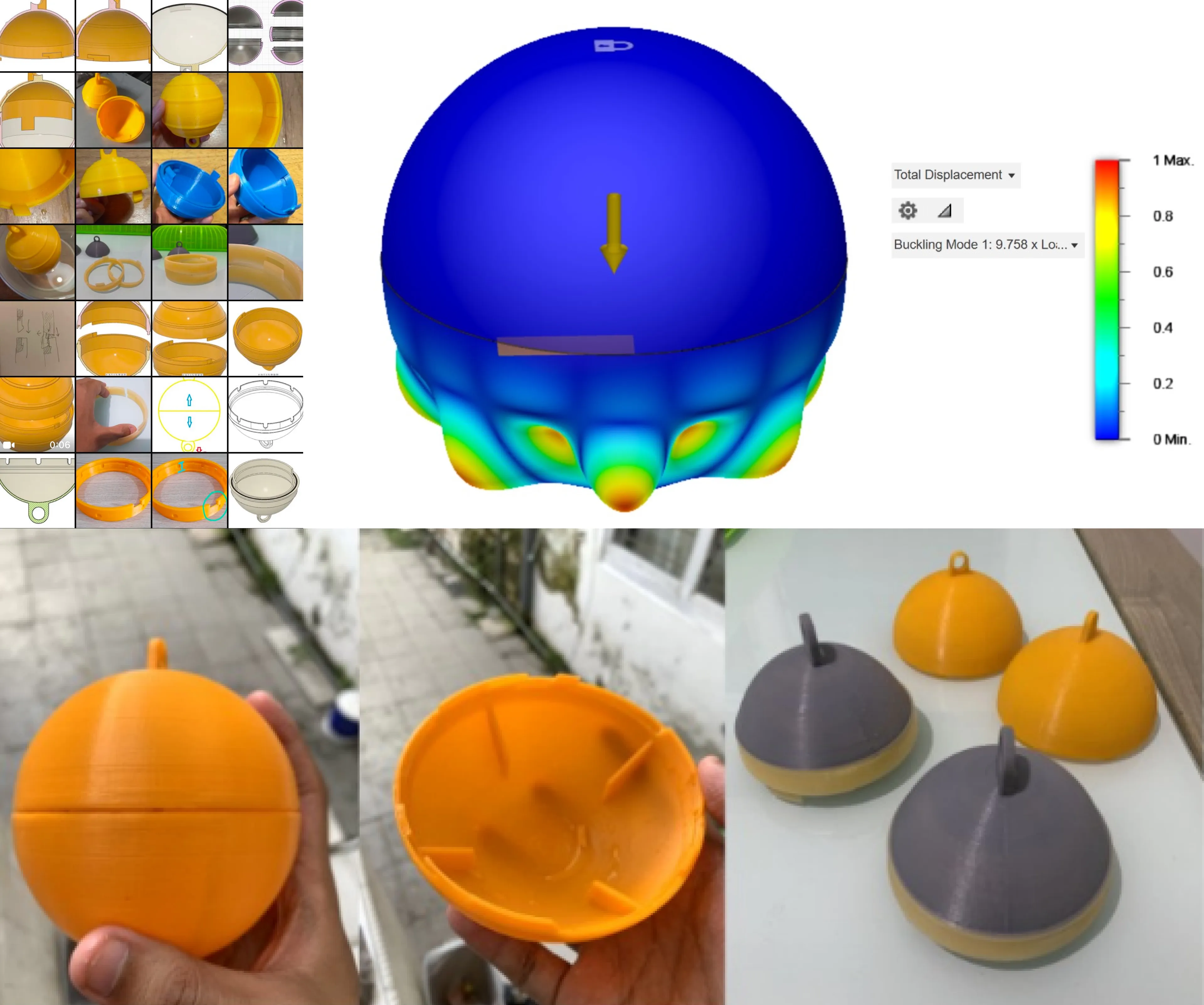

I used Fusion 360's stress testing feature to test how the buoy might behave in water under pressure and wave motion. The simulations helped us estimate possible buckling or bending of the shell, check the centre of mass and stability, and adjust the geometry before committing to a physical mould.

3D Printing

We then 3D-printed full-scale prototypes using FDM and SLA printers to check water tightness, ease of assembly, and the practicality of the locking system. These tests in real water allowed us to refine tolerances, confirm that the halves could be joined quickly in the field, and verify that the final form worked as intended before moving to metal tooling and production.

Tool Making

Crusher

We used a plastic crusher based on the open-source Precious Plastic standard, but assembled from locally available components. The machine shreds collected bottle caps into small, consistent flakes that can be fed into the injection machine. Designing it this way keeps the system familiar to the Precious Plastic community while making it easy to repair with off-the-shelf parts in Selayar.

Injection Moulder

For forming the buoy shells, we used a manual hand-press injection machine adapted from the Precious Plastic project. Instead of a large industrial setup, this low-power device heats and injects the plastic flakes into our metal mould through a simple lever mechanism. It allows local operators to run small-batch production safely, with clear control over temperature, pressure, and cycle time.

Welder

The only fully custom machine in the system is the buoy welder, which I designed myself. It uses a circular heating element to gently melt the edges of two buoy halves and then press them together, sealing the joint without any mechanical locking mechanism. The motion is a simple vertical slide, perpendicular to the buoy, so users only need to align, heat, and press. My approach keeps the tooling compact, tolerates variations in recycled plastic, and creates a strong, watertight bond with minimal moving parts.

Testing & Commisioning

Testing

We ran a series of trials to test both the machines and the buoy design before bringing them to Selayar. We experimented with different plastic types and conditions, including pure HDPE, degraded beach-collected HDPE, PP, and PET, to see how each behaved during shredding, melting, and moulding. Using CNC and EDM machining, we iterated on the metal mould so it could accept this wide range of material qualities while still producing shells that were watertight and structurally stable. During these tests we also refined the injection and welding parameters, checking for leaks, cracks, and ease of demoulding.

Commisioning

After the lab trials, we carried out a one-week commissioning programme on Selayar Island. Together with local partners, we installed the crusher, injection machine, and custom welder, then held hands-on training sessions on cleaning coastal plastic, shredding it, operating the machines safely, and inspecting the finished buoys. Community members practiced each step themselves, from feeding the crusher to welding the buoy halves, and we used their feedback to adjust workflow and documentation. We ensured that, after we left, the system could be run and maintained locally as a small, community-owned production line.

What did I learn?

Our commissioning worked better than expected!

The production line ran almost flawlessly. Instead of the planned two weeks of training, the community in Selayar understood the machines, stabilised the process, and started producing buoys in under one week.

Their creativity surprised us...

The people of Selayar, whose perspectives are rarely heard in conversations about technology and design, were far more inventive than we expected. During training they immediately asked whether the same mould could be adapted for other objects, such as souvenirs, which opened new ideas about reusing the tooling beyond buoys.

Remote communities have strong untapped potential.

I realised that communities like Selayar just lack access to technology. Their skills and ideas are rarely heard in mainstream design and tech conversations, yet with simple, repairable machines and the right productive and educational resources, they can move toward economic self-sufficiency using their own materials and knowledge.

What's next

Selayar showed me that a small, simple system can change how a community relates to its own waste. One island, one set of machines, and one basic mould were enough to turn discarded plastic into working buoys. This makes me want to test the same approach in other coastal places, each with different materials and traditions, and see how far a family of small, repairable production lines can grow when local people adapt them for their own needs.

I am also curious about what happens when this way of making enters more visible worlds. The same process that quietly supports seaweed farmers might also shape objects that appear in city life, on bodies, in performance, or in exhibitions. I want to explore how a modest, community-based material process behaves when it moves from remote shorelines into spaces that care about form, style, and narrative, and whether it can carry its story of care and attachment with it.