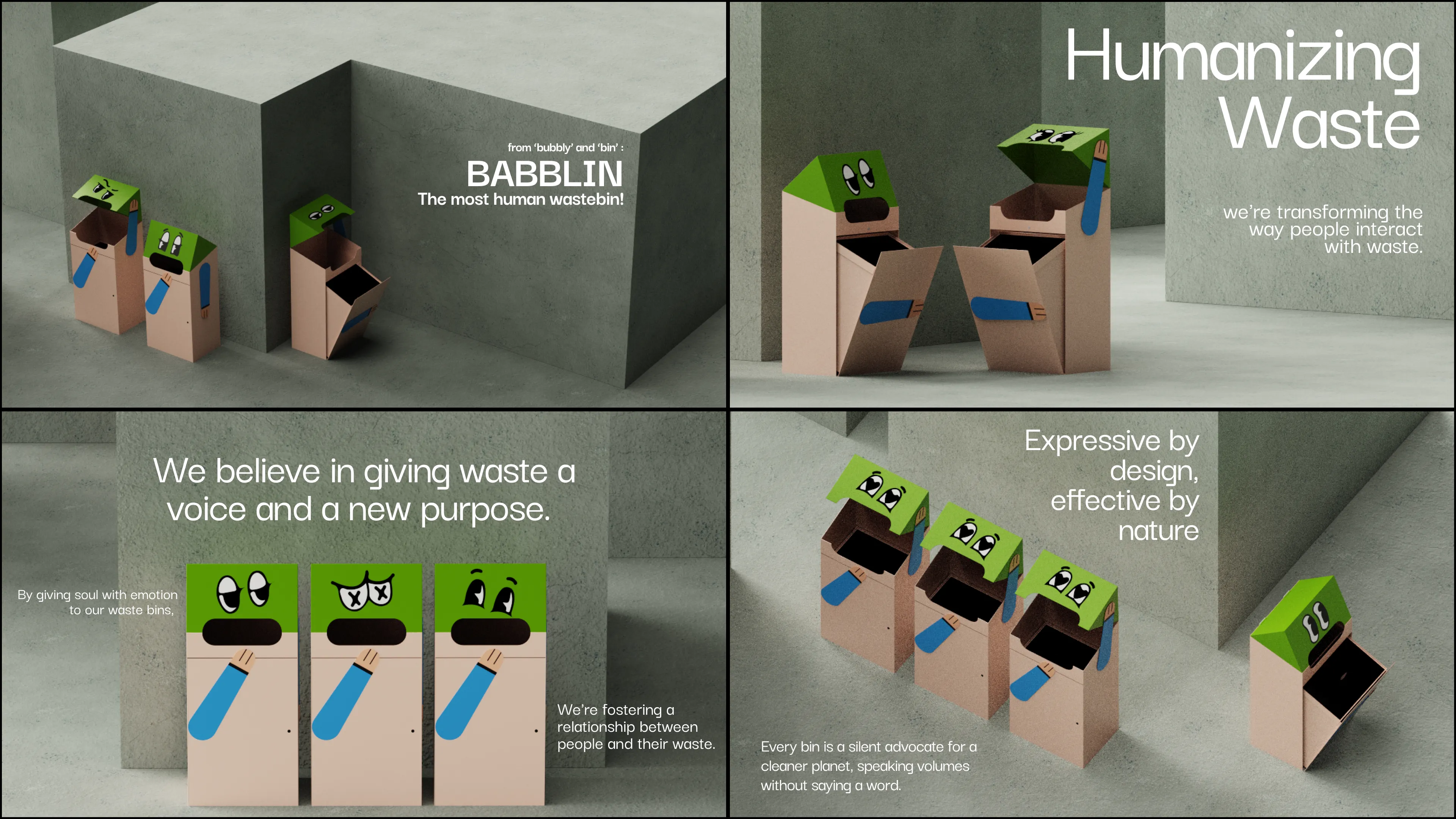

Babblin Wastebin

I created BABBLIN, a waste bin with playful anthropomorphic eyes powered by AI so the bin responds to the context of where it is placed and feels more like a character than a cold object.

2025

—Laurensius Rivian Pratama - Product Designer

Roles

My Role

- - Sole product developer from first concept to final prototype

- - Designed the bin body, anthropomorphic faces, and graphic system.

- - Developed the contextual “eyes” logic and AI pipeline.

Theoretical Lens

- Urban play

- Behavioral nudging

- Anthropomorphic design

Methodology

- Frugal engineering

- Behavioral observation

- Context mapping

Background

Many people in my city already live with waste every day, yet screens rarely reach them in a quiet, reflective way. I wanted to move the conversation out of the tablet and into the street, into the short moments when someone walks past a corner, throws something away, or waits for a ride. During my research visits with Waste4Change I kept noticing how public bins sat in the background like mute infrastructure, even though they held the most direct contact between citizens and the waste system. They were everywhere, yet almost invisible.

Through BABBLIN, I wanted to see what happens when a very ordinary bin begins to look back, when it has eyes, gestures, and a bit of personality that responds to context where it placed. The goal is to nudge them into a tiny moment of attention so they notice the object, the act of throwing something away, and the material story behind that object. BABBLIN became my way to test how a small, approachable character in urban space can carry some of the systemic questions from Upcycled 2045 into everyday life without asking anyone to pick up an iPad.

After the video game, I wanted a more scalable way to talk about waste, so I turned to urban space medium and asked how a very familiar trash bin could feel more friendly and intimate.

Overview

This project development started from a practical brief at Waste4Change. Management asked for a sorting bin that clients could manufacture cheaply through local workshops using simple sheet metal and off the shelf parts while still looking distinct from the usual public bins. I kept noticing how littering gathers around predictable pressure points such as takeout zones transit edges and informal street markets where people move fast and no one wants to carry packaging any longer than needed. The goal became a bin that stays straightforward enough for large rollout while adding a small expressive layer that can pull attention at the exact moment someone decides whether trash stays in their hand or becomes part of the street.

Main Concept

Correlation between Littering and Social Signals

Many researchers have shown that cause of littering is because of how a place is organised and understood. Mary Douglas described dirt as “matter out of place”, so rubbish becomes a sign that boundaries and meanings in a space have broken down (Douglas, 1966). Work in environmental psychology shows that people copy what a place seems to allow, so visible litter, busy food streets, weak bin presence, and vague rules together raise the chance that more trash will appear (Cialdini et al., 1990; Schultz et al., 2013). Urban theory adds that streets work as social stages shaped by flows of workers, students, tourists, and informal vendors, and that small signals of care or neglect can shift how people act without any law changing in the background (Wilson and Kelling, 1982; de Certeau, 1984). Litter, in that sense, is a symptom of how geography, infrastructure, and local culture interact, and any design that wants to change it has to speak to that whole system rather than to individual behaviour alone.

Contextual eyes gaze

The idea of contextual eyes started from a simple frustration with how public bins usually communicate, like I want them to shout 'Hey, let me take your trash!'. I wanted the bin to behave more like a local character that understands where it stands. Eyes became the lightest way to do that. People search for faces in objects and follow where eyes look, which means two small circles can draw attention, mood, and presence without a single word. The question then shifted into whether a pair of eyes on a bin could acknowledge the street around it and invite a small emotional response instead of another moral lecture about trash.

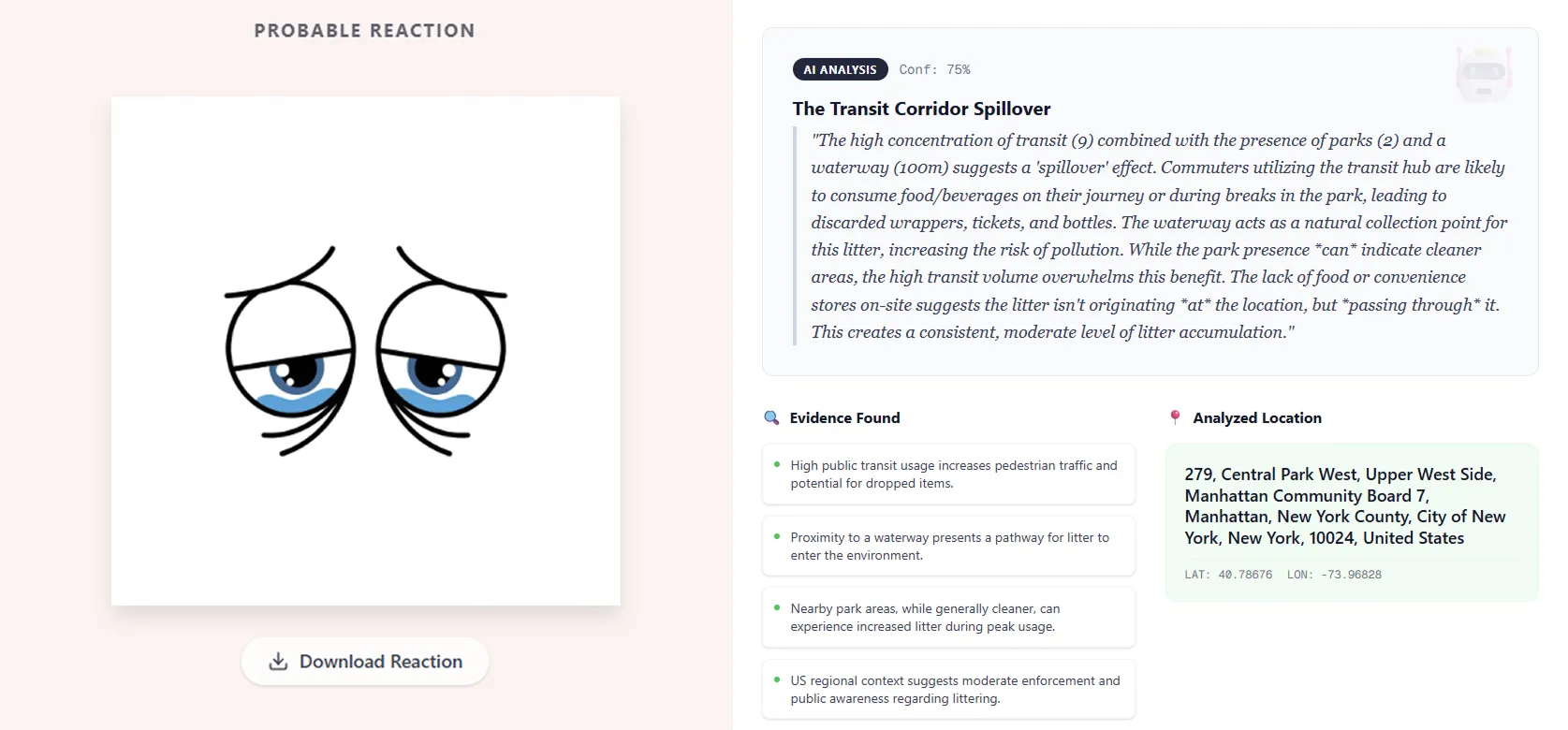

To achieve this, I use AI deduction which treats every street corner as a bundle of social signals. Instead of analysing camera images, the system reads nearby restaurants, transit stops, waterways, and parks, then mixes that with regional habits about litter and cleanliness. The bin’s eyes become a tiny interface for that hidden analysis, for instances, a nightlife street might get slightly overwhelmed eyes while a quiet park corner might have calmer or more curious eyes. The work sits between urban play, anthropomorphism, and critical surveillance theory. The goal is to see whether a passive-responsive object that quietly mirrors the pressures of its environment can change how people relate to everyday infrastructure and make small acts like sorting waste feel more like interaction than obligation.

Technical Details

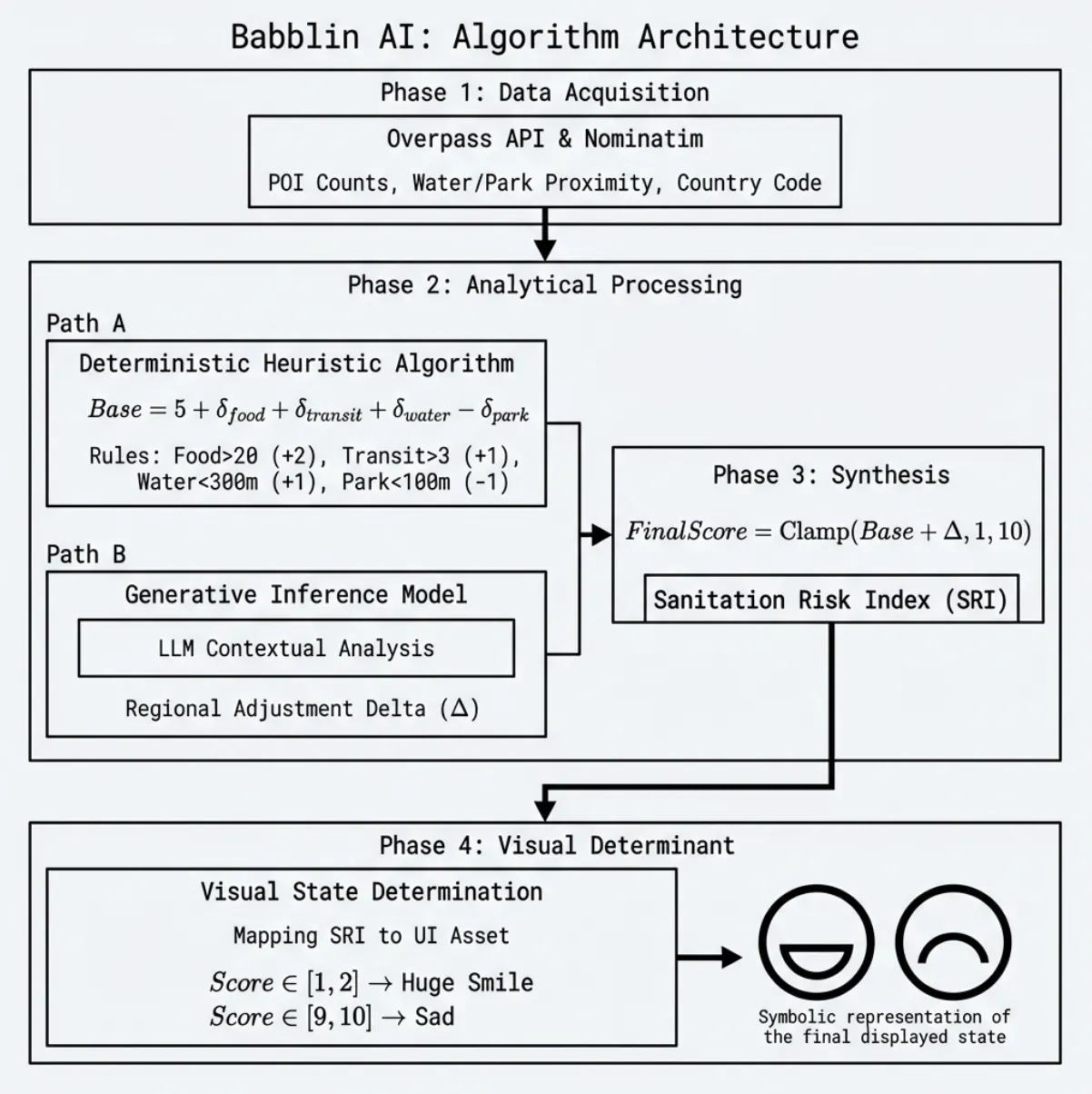

How the passive-generative design works? Babblin uses a passive responsive loop where the intelligence happens before installation and the “response” becomes a printed surface. A location goes in and a face comes out, then the face gets printed as vinyl and applied to the bin. No sensors, no cameras, no power draw on site. Updates happen through reprints, which keeps deployment light and maintenance realistic for public infrastructure.

The pipeline begins with a place name or a pinned point on a map, which together these signals form a compact location fingerprint :

- The system resolves the input into latitude and longitude.

- A reverse geocode step retrieves the country code.

- The country code helps the system account for local norms that shape litter patterns.

- The system scans the surrounding area within a walkable radius using OpenStreetMap queries.

- The system avoids imagery and relies on proxies for human activity.

- Restaurants and takeout nodes indicate likely packaging volume.

- Convenience stores and supermarkets indicate single use purchases nearby.

- Transit stops indicate crowd turnover and waiting behaviour.

- Distance to waterways models a sink effect where light plastics drift and accumulate.

- Nearby parks act as a management proxy linked with cleaning cycles and bin density..

A deterministic scoring layer turns the fingerprint into a baseline risk score so results stay anchored in explicit logic. The AI layer then takes over for interpretation and calibration. The model receives the baseline plus the proxies plus the country context, then it produces a cultural adjustment and a short causal story that connects the proxies into a plausible street narrative. The output does not create visuals. The output selects meaning and tone, then hands off a final score and a small set of drivers that explain what pushed the score up or down.

A mapping layer converts the final score into a reaction id that points to a pre-rendered eye asset library. That choice is deliberate because it keeps the aesthetic consistent and avoids unpredictable image generation. The print compositor pulls the matching high resolution asset and exports a production ready file with fixed dimensions plus bleed plus cut contours for sticker cutting. Vinyl choice matters for outdoor bins so UV resistance and laminate spec belong in the pipeline, not as an afterthought. The last step is physical, where the sticker gets applied to the bin, which turns location context into a readable expression that lives in the street rather than on a screen.

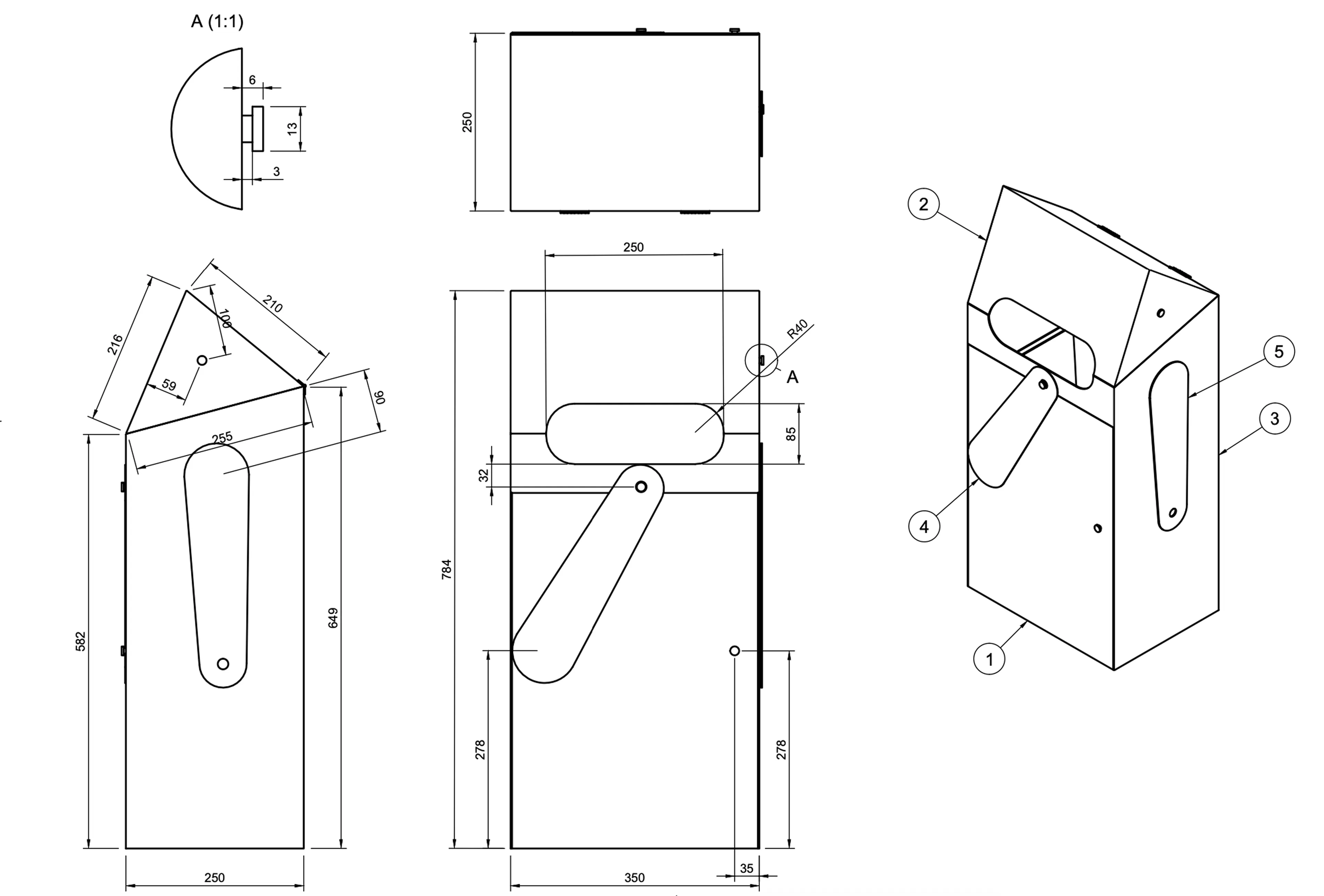

How we fabricated it

I started the development with durability and simple manufacturing in mind. Stainless steel became the main structure because it handles daily contact and routine cleaning and it stays rigid at thin gauges so the bin can hold a 50 litre capacity without bulky thickness. Grade 304 was prioritised for outdoor or coastal placement where humidity and salt raise corrosion risk and Grade 201 stayed as a cost aware option for sheltered sites. A powder coated finish was chosen to protect the surface from scratches and to keep maintenance simple because dirt lifts faster from a sealed coating. Weather proof targets shaped tests around seams and door edges and drainage paths so rain does not sit in joints and the graphics stay legible. The internal layout stayed modular so a single body can support an optional multi compartment format and the mounting system stayed flexible so installations can be fixed in place or set up as portable units for temporary deployments.

Manufacturing

Local Workshop

I learned very quickly that our metal workshop production capability were the big constraint. CNC routing was far too expensive for our budget and laser cutting was still costly, so any design that depended on complex curves would kill price competitiveness against standard bins with the same volume. I started from the way sheet metal is actually cut and bent by small workshops and looked at simple origami folds for reference. Flat panels with straight lines can be cut with manual power tools and then folded into shape, which within that shape limitation I tried to make the overall styling to be as expressive as possible (bubbly eyes and handle that resembles hand) so the bin looks like human. The goal was to stretch low tech fabrication to its edge and still arrive at an anthropomorphic object that feels distinct in the street.

What did I learn?

The dilemma of impact and scale... The product now exists in the market and competes on price and durability with standard bins, yet the real environmental impact depends on reaching procurement scales where whole streets or districts adopt it instead of treating it as a niche option.

Misread playfulness? Many people respond to the bubbly eyes as simply “cute” and stop there, which shows how easily a critical idea can be absorbed as decoration and reminds me that future versions need clearer cues, stories, or interactions so the underlying message about waste and care does not disappear.

Towards sentient objects! Working on Babblin expanded my interest in object oriented ontology because the AI pipeline hinted that even a simple bin can hold a kind of situated intelligence, and this opened a path toward designing more urban objects that speak back and reshape how people relate to the inanimate world.

What's next

This project showed me that a bin with playful eyes can open a small moment of curiosity, yet most encounters stay fast and shallow. Many people think it looks cute and then walk away, and the deeper questions about waste, place, and responsibility vanish in a second. That experience makes me want formats where objects can hold attention for longer, share richer stories about their lives in the city, and invite people to stay with them rather than toss something in and move on.

The next step for me is to give everyday furniture and street elements a speaking role so people can listen instead of just glance. I want to use AI as a narrative engine that writes from the point of view of the object, so each piece becomes a slow conversation about its place, memory, and care.