Sitting with Jakarta

I developed Sitting with Jakarta as an art exhibition concept where a chair tells its own life story as a sentient being, with memories, personality, and a view of Indonesian society shaped by different owners and places.

2025

—Laurensius Rivian Pratama

Hilwa Alifah Azzahra

Shafa Chairunida

Roles

My Role

- - Developed the core concept of a sentient chair that narrates Jakarta through its own memories

- - Wrote and refined the AI prompts that drive the intelligence analyst and chair consciousness personas

- - Defined the data structure for slides, generated images and the final cultural analysis card

Theoretical Lens

- Object ontology

- Material culture

- Urban memory

Methodology

- Narrative prototyping

- Prompt engineering

- Experience testing

Background

I realised something important from the previous project. People liked the bin, they smiled at the bubbly eyes, they said it was cute, but most of them did not really think about why the object was watching them or what it said about their habits. The interaction was fast and playful, and I started to see the limit of that approach. I wanted a slower moment where people stay with an object, sit down, look at it, and have time to think. That thought pulled me away from street furniture and public bins and moved my focus toward everyday chairs that quietly stay with people for years.

That thought pushed me to look at the objects that stay closest to us for the longest time. Chairs felt like the right focus. They quietly hold bodies, witness conversations, watch families grow, and carry traces of class, taste, and history in a city like Jakarta. I began to wonder what would happen if a chair could speak about what it has seen. That question became the seed of Sitting with Jakarta, where I explore how narrative and AI might give everyday furniture a voice, and how that voice could gently shift how people see their own relationship with the city and its objects.

After BABBLIN, I wanted people to become even more contemplative about their surroundings through storytelling rather than only through simple visual cues.

Overview

My friend Hilwa came to me one day with an idea for a chair exhibition. She showed me photos of jugaad furniture that street and homeless communities had built from scrap wood, broken pipes, and discarded parts, almost like Frankenstein chairs assembled from what the city left behind. At first I saw it as a nice visual concept but not very interesting for me. But someday, I was sparked with idea from the Babblin project. I began to wonder what would happen if I wanted the chairs to act more like a medium, almost like a 'ouija board' for daily life in Jakarta?

Main Idea

Introduction of Object Oriented Ontology

Object oriented ontology gives me fresh perspective to think about chairs as more than tools that support human bodies. Graham Harman (2018) argues that every object withdraws from full access, whether a person, a chair, or a city, so our contact with things is always partial. Ian Bogost (2012) invites us to imagine how objects relate to each other instead of seeing them only as background for human stories. Jane Bennett (2010) writes about vibrant matter and shows how non human things can shape moods, choices, and events. Together these ideas shift the focus from what objects do for humans toward how objects exist with their own histories and agencies.

Why Chair

Once humans started walking on two legs, we began building simple supports for rest, work, and gathering, so chairs became one of the oldest tools that organize bodies in space. A throne in a palace, a plastic stool in a street food stall, and a broken seat in a bus stop all carry traces of who sits there, how long they wait, what kind of life passes by. Chairs hold family dinners, office overtime, hospital vigils, first dates, and political decisions, so they become a kind of silent witness of human civilization. I see chairs as patient recorders of the city which absorbed stories in their scratches, stains, and repairs, even when nobody is paying attention.

Core Message

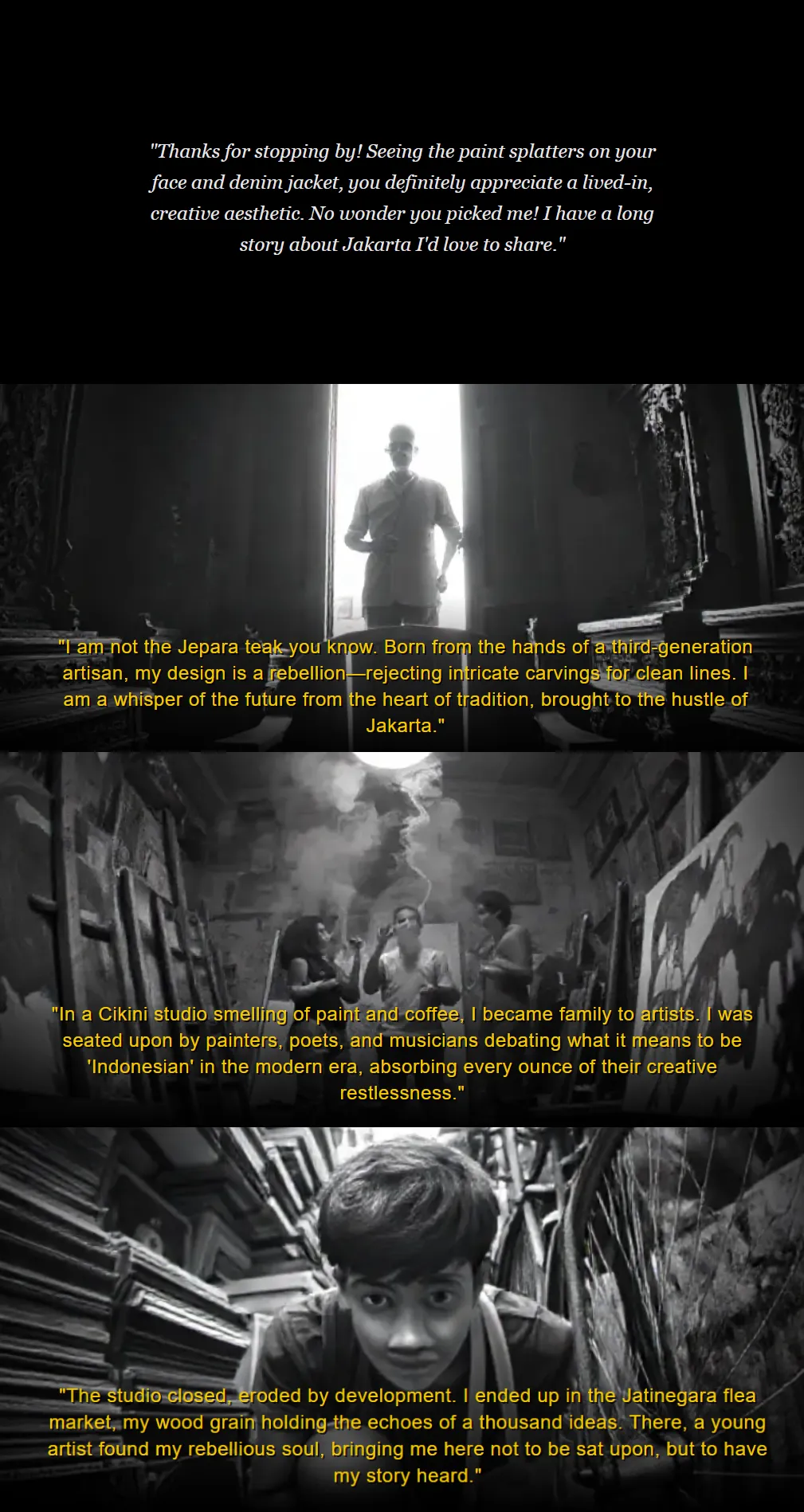

The project asks visitors to see a chair not only as furniture but as a witness that has carried tired bodies, hosted family talks, waited in offices, and sat through traffic noise and flooding. When the chair speaks through AI, it tells stories about where it has been, who has used it, and how the city has changed around it. The mirror and projection create a triangle between the visitor, the chair, and Jakarta, which invites people to notice their own posture, habits, and class position while hearing the story of an object that usually stays silent.

At the same time the work questions who gets to speak in a city shaped by inequality and overconsumption. Many people in Jakarta sit on broken or improvised chairs that never enter design museums, yet those chairs hold dense emotional and social histories. By giving narrative agency to a single chair, the project hints at the countless other objects that never get a voice. If we can extend empathy to a chair and take seriously the story it tells, maybe we can also shift how we relate to our surroundings, slow down our consumption, and build a more caring relationship with the material world that holds our daily lives.

Technical Details

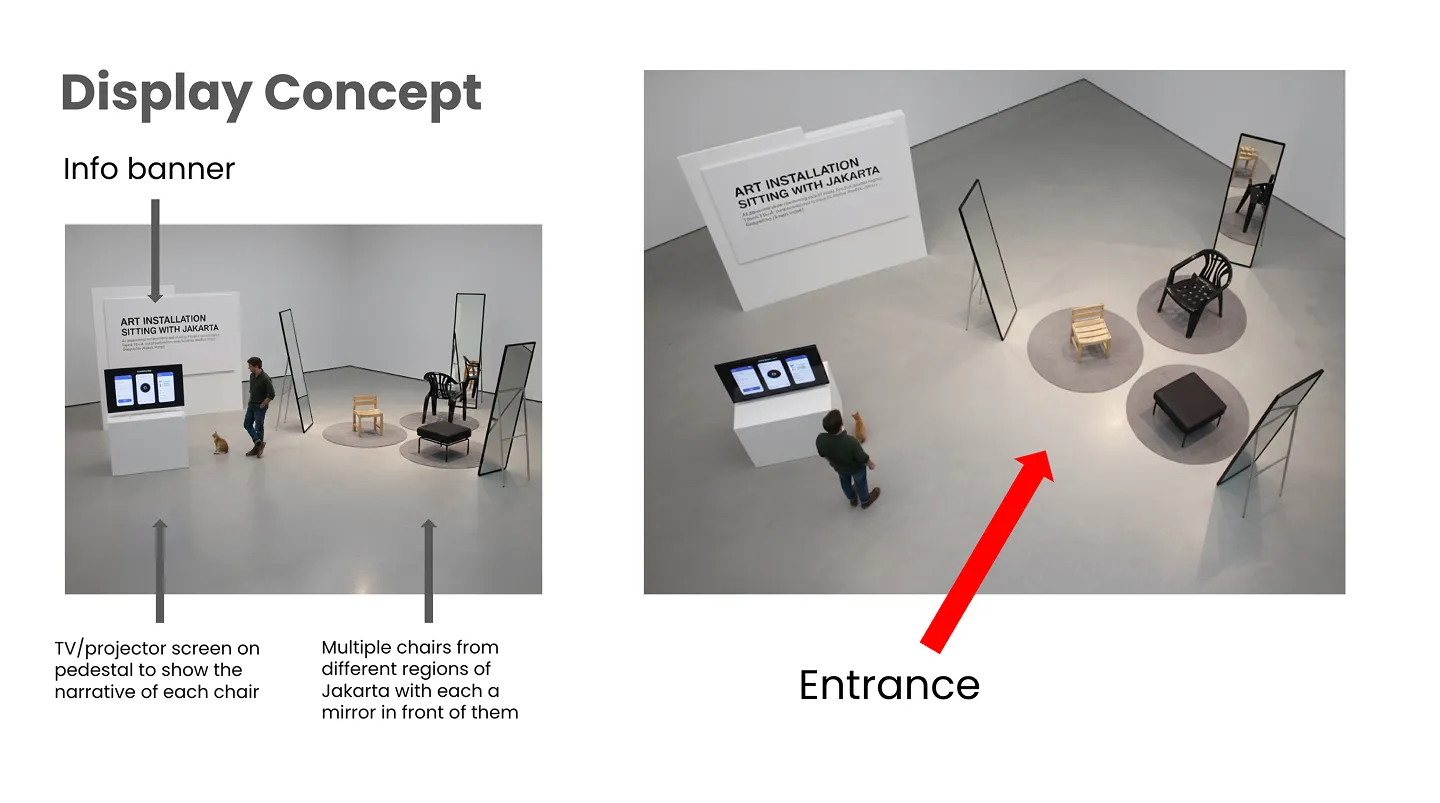

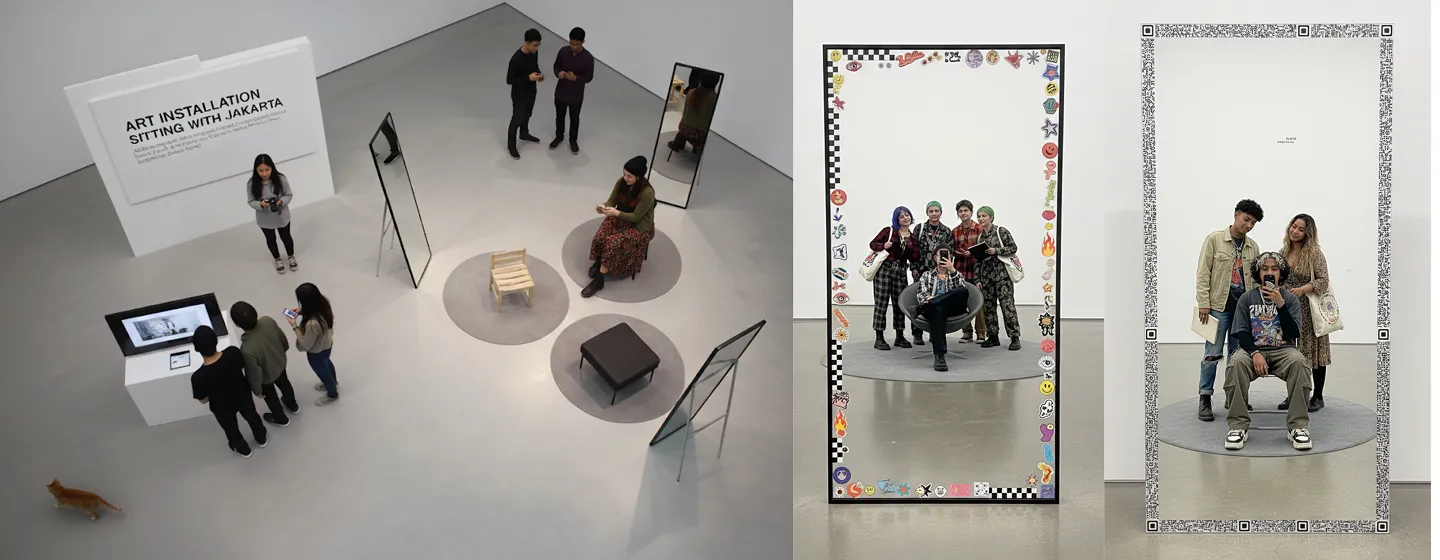

Spatial Layout A visitor enters and first sees a row of worn Jakarta chairs presented almost like portraits. Each chair faces a mirror that hides a webcam behind two way glass, so the mirror works both as reflection and as sensor. A small trigger button sits near each chair as capture trigger. On one side of the room the chairs and mirrors form an intimate zone where one person at a time can sit and look back at themselves with the object. On the opposite wall a projector throws the generated narrative as a slide show, so the story is visible to everyone in the space. The blocking keeps the chair, the human body, the mirror, and the projected text in one visual triangle, which turns the whole gallery into a conversation between person, object, and city.

Interaction Flow

A. Visitor walks along the line of chairs and chooses one that catches their attention.

B. Visitor sits, looks into the mirror, and sees their own reflection framed together with the chair.

C. Visitor presses the button, which quietly triggers the AI system to generate a new story for that specific chair and that specific encounter.

D. After a short pause, the narrative starts to appear on the projection wall as a sequence of slides, like a slow subtitle stream about the chair’s life in Jakarta and the new memory created with the visitor.

E. Visitor can stay seated to read, stand up and move to the shared viewing area, or step away and let the next person sit while the story keeps running.

The spatial flow encourages people to move from private contact with the chair, to shared reading of its story with others, so the blocking supports the idea that a humble piece of furniture can hold both intimate and collective memory.

AI Algorithm

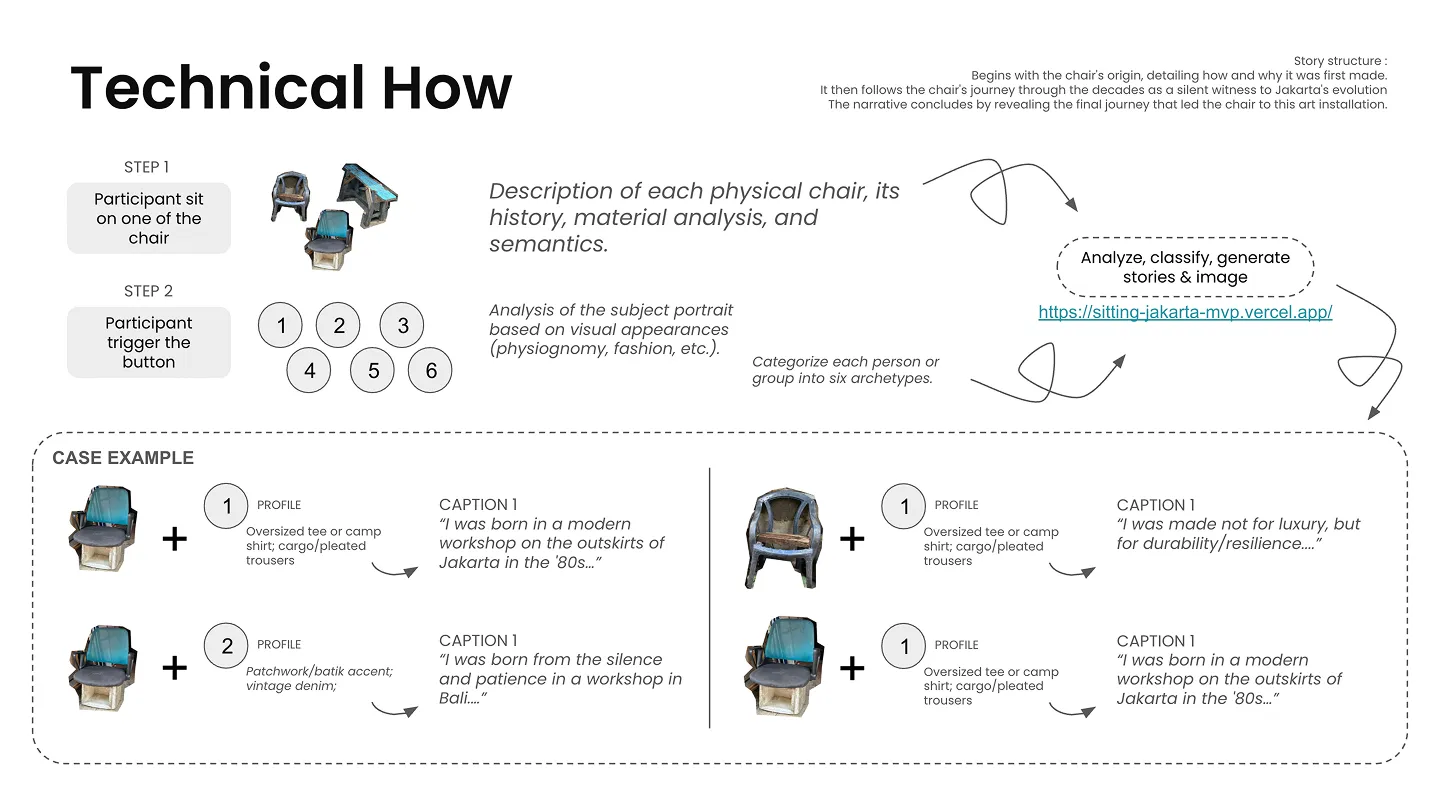

The algorithm tries to infer how the person moves through Jakarta, how they use furniture, and which domestic and public spaces they probably occupy, based on their overall appearance using physiognomy theory.

We want to create a believable story for a Jakarta chair that has known the visitor. After they click a trigger button, the system passes the portrait of the visitor to an AI that plays the role of an physiognomy analyst. That analyst reads the face, clothing, grooming, and visual hints in the background, and then writes a dense profile of the person. The profile includes guesses about class position, lifestyle, habits in the city, and emotional posture. All of that becomes a structured text report that the next step can read.

The second layer of the algorithm mixes that profile with a fixed profiling data that defines the personality of each chair type. Each chair has a small ontology that describes its typical locations, owners, and social meaning in Indonesia. The system feeds both the human profile and the chair identity into a storyteller agent that writes a six part autobiography. The timeline often runs from the chair’s “birth” in a workshop or factory, through different homes, shops, schools, small stalls, and finally to its late stage in storage or on the street. The writer agent aligns the user’s inferred background with plausible scenes in Jakarta. A middle class student might meet a bimbel chair in a cram school. A market worker might meet a plastic stool in a food stall. The output is strict JSON that includes six text slides plus six short image prompts.

The last step turns those prompts into images that stand in for what the chair would see if it had eyes. Each prompt goes to an image generator such as Flux Schnelland returns a scene framed from the chair’s imagined position in the room rather than from a human gaze. Post processing with blur and greyscale softens the sharp AI output and pushes the view toward a hazy recollection, as if the chair remembers bodies, rooms, and light but not exact faces.

The whole chain of pipeline from portrait to story becomes a compact simulation of an inanimate object point of view.

What did I learn?

Still remain a proposal

The work still remains as a proposal and phone based demo, which makes the gap clear between a working narrative engine and a full physical installation with mirrors, cameras, and projection. I still need to learn about production planning, hardware integration, and working with institutions if I want this kind of piece to exist in public space.

Potential of AI

Building the chain from analyst to sentient chair showed me how AI can become a narrative partner that links faces, places, and objects into one continuous story. The system can hold very local Jakarta details while still improvising new scenes for each visitor, and makes the AI more like a flexible medium for intimate, object centred storytelling.

What's next

A single image gives surface hints about mood, style, and social position in uncanny way. After working with that I started to wonder what might happen if the system could read data that feels more personal than a face. Once I saw how far a model could go using only a portrait and a chair archetype, I became curious about what kind of mirror it could build if it had access to richer patterns from everyday life, and how far should it go.

That question pulled my work toward more intimate forms of interaction. I wanted to explore systems that use personal data as narrative material which people can do reflection that people would normally avoid having with themselves. The goal is to see whether AI can become a careful companion that reveals blind spots while also exposing how much of our inner world is already legible to machines. From there I became interested in building an experience where care, exposure, and control start to blur, so people can sense both the comfort and the danger of letting technology know them too well.